Dr. Finn Wolfreys, University of California, San Francisco, USA

A Short Biography of Antibodies

Our character’s story may well begin with life itself. Though the exact moment is a little hazy. At some point there were atoms, and some atoms, more stable together, persisted as molecules. Then our molecules must have assembled into chains that were copied. How it transpired is not yet untangled. Only that the copies were not perfect. Otherwise our story would already be over. Occasionally a new chain must differ ever so slightly from its parent. Whether it will be for better or worse we don’t know, but nature and time will take care of that. And so our humble chain will continue, for generation upon generation, slowly guessing at improvements, until it barely recognizes itself. Though you will know it as life.

At least, this is one story. Whose unlikely serendipity our antibody will soon retell. Albeit with more characters. One will be familiar though, as its ancestor is our chain, which now reaches a length of several billion molecules, though they take only four forms: the four bases of DNA. But this is no limitation, because their sequence directs the assembly of more complex chains, proteins, which accept molecules of 20 designs. When assembled, for reasons that must be narrated elsewhere, the protein chain will begin to fold, until it no longer resembles a chain, but a shape. A shape that places exactly the right atom in exactly the right place to, for instance, join molecules, or tear them apart, or execute whatever operation evolution finds need for. It is among these shapes, functions, and stories, written in DNA, that we will meet our protagonist.

First, though, our chain must find a lipid shell, which will become a cell. And during its ascent, when guessing at improvements, occasionally the answer should be ambiguous, so that life diverges and is preserved among domains, kingdoms, phyla and so on. However different, their complex characters will all narrate the same plot of self-preservation. At times it will manifest in cooperation, so that eventually our cells ally into multi-cellular organisms. But often the preservation of one branch will be at odds with another, causing our organisms to place on evolution the burden of protection, whose dilemma will be to discern self and non-self.

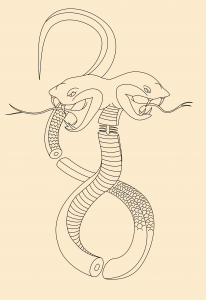

The problem is that of one molecule recognizing another, among countless similar. In time, instructions will be composed in DNA for certain proteins, which we will call receptors, whose folded chains recognize the molecular motifs common to non-self. But such receptors can only pursue their quarry at the slow pace of evolution. Perhaps it was impatience with the nimble evolution of our adversaries, or perhaps it was just luck, eventually though, evolution saw cells begin improvising new receptors; among them, antibodies. Of course, improvisation is not so much original composition as unique editing, so antibodies are built from DNA templates. These templates define two protein chains, named, for their size, heavy and light. In each antibody molecule are two identical heavy chains, and two identical light chains. When assembled, they will appear like a snake with two identical heads, engineered to engage their prey by complementing its surface, attracting it, as if it were charmed.

The problem is that of one molecule recognizing another, among countless similar. In time, instructions will be composed in DNA for certain proteins, which we will call receptors, whose folded chains recognize the molecular motifs common to non-self. But such receptors can only pursue their quarry at the slow pace of evolution. Perhaps it was impatience with the nimble evolution of our adversaries, or perhaps it was just luck, eventually though, evolution saw cells begin improvising new receptors; among them, antibodies. Of course, improvisation is not so much original composition as unique editing, so antibodies are built from DNA templates. These templates define two protein chains, named, for their size, heavy and light. In each antibody molecule are two identical heavy chains, and two identical light chains. When assembled, they will appear like a snake with two identical heads, engineered to engage their prey by complementing its surface, attracting it, as if it were charmed.

The genesis of our beast occurs in the bone marrow. From a cell whose progeny have two fates: to remain a clone of their parent, or to specialize towards a new function. Our cell will take chemical and physical cues from its compatriots, and choose the latter. Although it shares the DNA of its parent, which traces its lineage to the beginning of our story, our cell will re-examine it. It will begin to assemble a different set of molecules. Some of which will themselves examine its DNA chain in search of antibody templates, parts of heavy chains and parts of light chains. And they will begin to cut and splice until, from the templates, they assemble a heavy chain which is, by overwhelming probability, unique.

Our cell is now engaged in becoming a B cell. Though it will seem almost indistinguishable next to its parent, the proteins decorating its surface are beginning to change. Among them is a new heavy chain. Though not on every cell. Such is the will for molecular diversity, that our recombination must permit errors, which will prevent many heavy chains from being assembled. The story for these cells will shortly end with their sacrifice, or apoptosis, as the euphemism goes. But those remaining, will begin to divide, sharing their new heavy chain with their progeny, who will begin combining templates for a light chain. Soon, the whole antibody will appear, heavy and light chains, like a two-headed snake with its tail anchored to the cell surface. But it cannot hunt yet. Not in the bone marrow among friends. Though some will try. Should they escape, they would direct attack upon ourselves. They may be given the chance to change, but if the problem persists, eventually they will sacrifice themselves.

And so it is that a B cell generates a unique receptor for an unknown foe, and together these cells curate a repertoire of antibodies numbering, it is thought, in the billions (the exact number is still uncertain). Though however large, it is not enough to match every possible foe with precision. So for the purposes of our story, our B cell, which has now left the bone marrow and traveled by blood to the spleen, will set off again, until it detects a chemical beacon, and squeezing through a vessel, arrives in a lymph node. It is surrounded now by cells born in the bone marrow who have also traveled and changed, as well as some strangers. Each with their own stories.

A B cell’s improbable life is usually short, as it must make way for new B cells with new antibodies. But a pathogen has been detected by its colleagues, who have now brought it to the lymph node in search of a receptor. And against all odds, our B cell’s antibody happens to recognize part of our pathogen. So in preparation for its final ritual, our B cell begins to divide, each of its progeny containing our special antibody, a novel receptor for a novel foe. But it is only a draft. In homage to the evolutionary selection that bore them, they begin making changes. This time to just a few molecules at the surface recognizing our pathogen. Still, such is the delicacy of engineering molecular recognition, many receptors will be rendered useless, and their B cells must be sacrificed. A few, however, may improve upon their design, and will continue an opaque choreography of editing and checking, supported by cells whose stories we cannot narrate. At the end, if we are lucky, a new antibody will emerge, much better than its predecessor.

Our original B cell is now gone, replaced by its successful progeny. Some will persist for decades as memory cells, storing the antibody they have happened upon, should it be needed again. Most, however, will begin producing their antibodies as plasma cells. Thousands of molecules per second. But our antibodies will no longer be tethered. Instead they will diffuse alone, as far they can. Until, by chance, they meet the surface they were trained on, that of their pathogen, to which their heads will stick, and after their tail is recognized by a fellow immune cell, their prey will be engulfed and destroyed. But even when it is all over, our antibodies will still patrol, should our organism meet the same foe again. And should they be overcome, the memory cells that preserve our antibody will perform the ritual of antibody selection again, in search of further improvement. Which is all to say, our organism is now immune.

But our antibody’s story is not over. Because our organism is now a human, who has noticed that cowpox protects against smallpox. And that there is something special in the serum of those who survive illness. Soon enough, our investigator will find antibodies, and then B cells, which they will immortalize in order to supply antibodies indefinitely. Eventually the DNA of heavy and light chains will be isolated, we will make changes, and antibodies will live a new life as drugs. So that the unlikely story of one B cell can save the life of many. But we will have to leave our story for now. Though it still continues, much like how we found it, with a chain, modified by evolution’s now distant hand, for self-preservation.